AFTER A POSTCARD

Christine Spillson

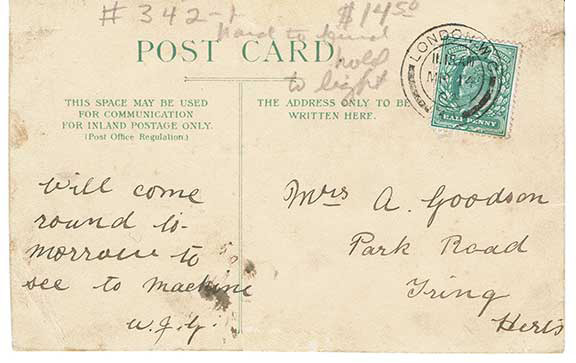

Will come

round to-

morrow to

see to machine

W.J.G

Now that it has been sent and

received and discarded, the brief note can only erode out of history and into supposition, context

dissolved in the solvent of time.

Though the postcard was gifted

because of the image on the front, it is the message, the seemingly careless, one line promise of a meeting that fascinates (that haunts it). Tomorrow, the writer stated, perhaps meaning: It can wait until tomorrow. Or: It cannot wait until the day

after that.

Tomorrow seemed like

an extravagant promise to be placed on the back of a postcard. What tomorrow would this be? The tomorrow from the sending or the tomorrow from the receiving and how could either end of this communication know for sure when

it would be tomorrow?

Postmark:

London. W.C.

11:15AM

MR 14

1904

It was, most likely,

meant to be tomorrow in the traditional sense. It was a promise for the day immediately following the day of the promise. Mail (it is easy to discover) was delivered approximately six times a day in that region, in that time. Send a dinner invitation in the morning, hear back by afternoon. This was a decrease from the dozen-time a day delivery of just fifty years earlier. How wildly efficient (the mail). How disappointingly precise

(the message).

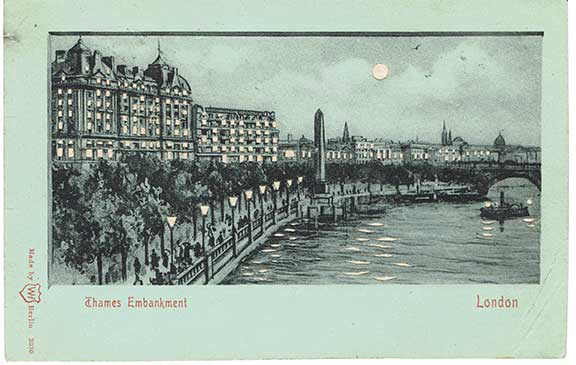

On the back, the fading

to faded black script—an ink blot coming close to obscuring the message, coming close to making this a mistake rather than a missive. On the front, a London scene. It is a view of the city from the river. The artist, it appears, must have been standing on a bridge whose position may or may not exist (I cannot determine it exactly). On the pale grey-green of the cardstock: the city, dark because it is night. The

city, dark because it is ink.

The image held

up to a light and the city is aglow. The yellow of the bulb transforming into the gaslight and candlelight in the windows of buildings. The paper has been carved into by bare millimeters, making parts thinner and more susceptible to transparency, etched by careful hands into glowing. Curved slivers of light emerge from the river, making the water move, cresting and restless, streaming from stillness

within the borders of the card.

(This was

what I once imagined was meant by illuminated manuscript. I imagined tiny perforations of light forming a picture in a text or, I imagined a painting as a palimpsest—

an image scraped away, hidden under words, only to be revealed by

light or flame or heat).

If sent a few years earlier—

the message could be read as explicit. It could contain, in its single line, an interestingly ungendered reference to the sexual organs of either men or women as machine was used in slang for both at the time. It could, then, be documenting an affair, an illicit encounter. It would explain the whimsy of the image, the feeling it evokes of closed rooms and candlelight, of dark evenings and dark figures by the river. The wording though, even taking into account the possible slang and the imagined need for secrecy, can only be seen as profoundly unromantic. There is no I only will. There is no you or your. The personal is stripped bare in favor of the pragmatism of action and intention. Perhaps this makes it less likely that

it was a love affair.

It is unlikely

the word "machine" is meant to refer to all of nature or to "the work of the whole of the world" even though the word has, historically, been used in both ways. The word has also been the human body, the "body" of humanity, the political body, and many

other bodies in varied usage.

There are people in the picture

and there is the river and there is a bridge, and buildings—one, it can barely be seen, has a sign that reads "Savoy Hotel and Restaurant", and, in front of that, positioned so that it shares the center with the moon: Cleopatra's Obelisk. It could be said that the structure is a machine (in the sense of "a material structure designed for a specific purpose, and related uses") of memory. The obelisk is not called Cleopatra's because she made it or had it made (this was Thutmose III), or because she had the hieroglyphs carved into it (this was Ramses II), but a machine, even one that works to extract something as fine as memory, cannot determine to what use it is put, it can only be put to use. Upon its erection in London, in 1878, a time capsule is placed into the newly constructed base. In the capsule there is, amongst other things, a hydraulic jack, a bunch of hairpins, a few tobacco pipes, a set of imperial weights. The obelisk, put to the additional task of memorializing a newer time

and smaller, more mundane machines.

__

![[ToC]](17_2toc_t_off.jpg)