REVIEW

Annie Guthrie, The Good Dark, Tupelo Press, 2015

unwitting

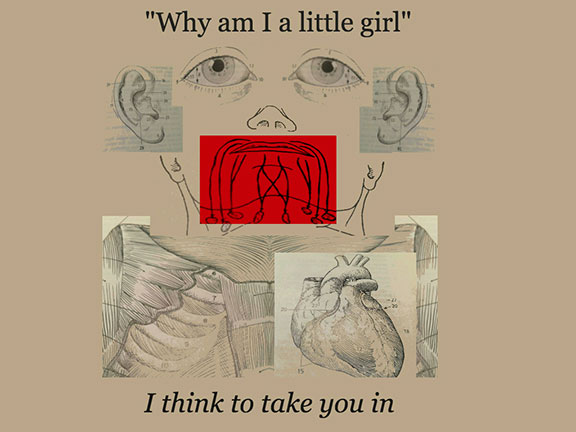

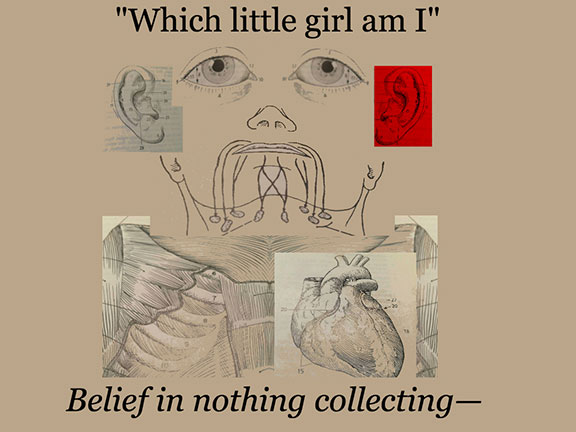

The Good Dark's entrance is the world. The world Annie Guthrie renders is aftermath echo, starting with the book's epigraph from Gertrude Stein's The World is Round: Why am I a little girl / Where am I a little girl / When I am a little girl / Which little girl am I.

Upon entering the mouth of "*weather'd," a cavernous sequence in its syntactical and mechanical methodology, we can callout: darkness.

"We" can be Guthrie's I and you. (And "*weather'd's" speaker officially questions you only once.)

After darkness, we can hear an echo of darkness—a wound sound sky that resembles our original call.

Though the echo in "*weather'd" is wound, flushed, fussing, and breaking, Guthrie also asks us to reorient this tangled rhetoric, gesturing toward an abstract, ghostly language; a timeless model. Language is unwound to reveal dark, sky, clouds, mouth, shape, and sound.

Still, Guthrie's dark offers an eye that looks closely at the wreckage newly reckoned. With this, we can lean on what's crystalline: doors, blender, bronze idol, claws, oily beak, ribbon, blade. These images, all of which have sharp defined edges, make Guthrie's world more habitable (and threatening).

The rules of the poem are revealed alongside Guthrie's eyed-up surface —, a passing landscape—. Her dense lyric entrance reaches and begs, which makes it also an entrance that we can hold and stroke down.

Yet

1. With can instead of may, hands bring rather than allow.

2. With not, we cannot step into a mistake.

3. Without no, silence can't be tested.

*

chorus

Guthrie advances her lyric with a chorus other than you and I. Titles reveal chorus members: "*," "*the gossip," "*the others," "*the priest," "*the reader," and "*the oracle."

Members act as matryoshka, working within and without one another to reveal or nest what's missing.

Because choral members' sections are braided unevenly, missing is cast in varying molds, and some members' casting is more insistent than others. Although "*the others" headlines with eight acts, "*the gossip" stands out because its mythic speaker oversees a she, always hinting at the inherent dangers (and pleasures) in finding what's missing.

This section asks us to sort out whom from whom in order of appearance gestures and juts.

"*"

The form is epistle, but it reads as ode: to a channel by land.

A speaker addresses missing with lost.

Consider again the helping verb could as a way to grapple with possibility. Is it possible the "*" is a self?

"*the gossip"

One must be careful to discern between outside and in!

Are we eavesdropping on she?

Consider an indicative conditional, an extrapolation of the she who is she and the I who is speaker.Promise: If I have to pull on the curtains, then she will understand the extent of my reach.

(a) Suppose that I have to pull on the curtains, and she will understand the extent of my reach.

(b) Suppose that I have to pull on the curtains, but she will not understand the extent of my reach.

(c) Now suppose that I do not have to pull on the curtains, and she will not understand the extent of my reach.

(d) What if I do not have to pull on the curtains, but she will understand the extent of my reach regardless?

"*the others"

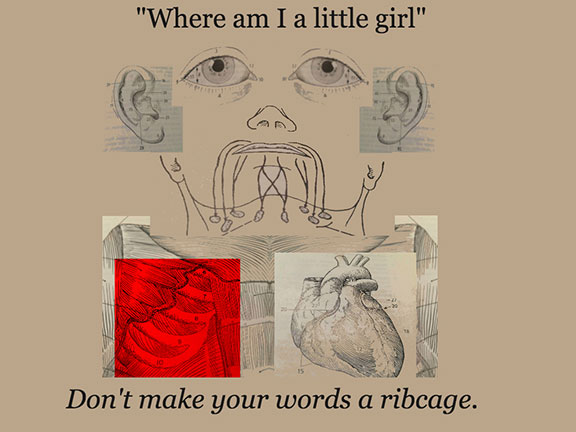

Text within text within text within: ribcage, us, one mirror, empty room, secret opening, whispers.

Awe as a question, a way of opening.

Consider imperatives and absolutes as a way to obfuscate: let's, nothing, don't, of course.

"*the priest"

Quatrains as in a test with four choices.

Quatrains as in "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner."

Consider the hinge in Part III, Stanza 13, lines 53-56: "The naked hulk alongside came, / And the twain were casting dice; / 'The game is done! I've won! I've won!' / Quoth she, and whistles thrice."

"*the reader"

Couplets juxtaposed with the spread.

Hand elucidates hands.

Consider tension in the third stanza's turn.

"*the oracle"

What/

?

Why

*

body

Whereas with the "unwitting" and "chorus" sections, Guthrie's speaker is aimed toward discovery vis-à-vis layering or circumnavigation, in "body," The Good Dark becomes more direct in its explorations.

Guthrie's speaker is unflinching in her confrontation of the world the selves in their most unkindred or unplucked.

A kind of dare is embedded within each question. The syntax is peculiar, as if it has outgrown its original guiding principles. Guthrie's neologisms mimic the feeling of seeing a shooting star. Slant rhymes act as navigational clues upon night's helm.

The corporeal I acts as a textual "medium," finding answers in the lines conjured by the body. Text surrounds the speaker (phrases frame / me), inscribing itself metonymically upon the body. We see the I, in one enjambed instance: typefaced.

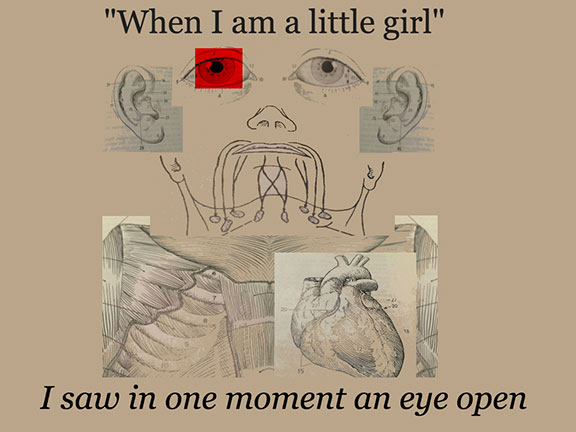

For Guthrie, this transcendence begins behind the pupil and thresholds with dark.

*

epilogue

[AF]

A note on the collages:

Assembled by Lawrence Lenhart, these collages compile illustrations by Gerhard Spitzer (Pocket Atlas of Human Anatomy, 4th ed.) and William L. Brudon (Essentials of Human Anatomy, 5th ed.), as well as text from Gertrude Stein's children's book The World is Round (above) and Annie Guthrie's The Good Dark (below).

![[ToC]](15_6_toc_t_off.jpg)